Since Labour came to power in 2017 the number of people relying on welfare has grown significantly, as has the time people spend dependent.

This development is due to both political ideology and political incompetence.

Finance Minister Grant Robertson makes frequent self-serving references to New Zealand’s low unemployment rate of just 3.2 percent. He does not talk, however, about the Jobseeker dependency rate which is much higher at 6 percent.

In absolute numbers 93,000 people are officially unemployed according to Stats NZ but there are 188,000 on a Jobseeker benefit.

It is unusual for the gap between the two numbers to be so large.

Four years ago, the respective numbers were close at 128,600 and 123,039.

To understand the growing gap, we need first to understand the definition of ‘unemployed’ used by Stats NZ which is:

– has no paid job

– is working age

– is available for work, and

– has looked for work in the past four weeks or has a new job to start within the next four weeks.

In contrast not all people on a Jobseeker benefit are required to be available or looking for work (a small fraction has part-time or seasonal jobs but that has long been the case.)

A crucial reason for the growing divergence is work obligations have reduced under the Labour government. The use of sanctions – the tool used to impose obligations – has dropped 66 percent in the same four-year period to December 2021.

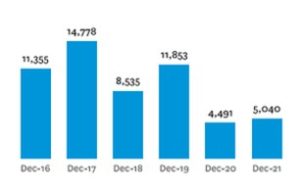

Number of sanctions for unfulfilled work obligations during the last six December quarters

Covid had some bearing but the reduction in sanctions pre-dates the pandemic. (Labour’s support partner, the Greens – who appear allergic to the idea of personal responsibility – would like to see sanctions abolished altogether.)

Without pressure to do so, some beneficiaries stop looking for work. If they aren’t looking for work, by Stats NZ definition they cannot be unemployed.

When Labour took over from National, they were intent on making the benefit system ‘fairer’ and set about diverting resources into contacting beneficiaries to check they were getting their full and correct entitlements. The answer to poverty was not a paid job – a 180 degree departure from predecessors Clark/Cullen – but getting more money out of the benefit system.

Resources were diverted from employment case management.

According to MSD’s 2018/19 annual report, “… only 20 percent of engagements with clients in June 2019 had an employment focus, the lowest proportion since 2014.”

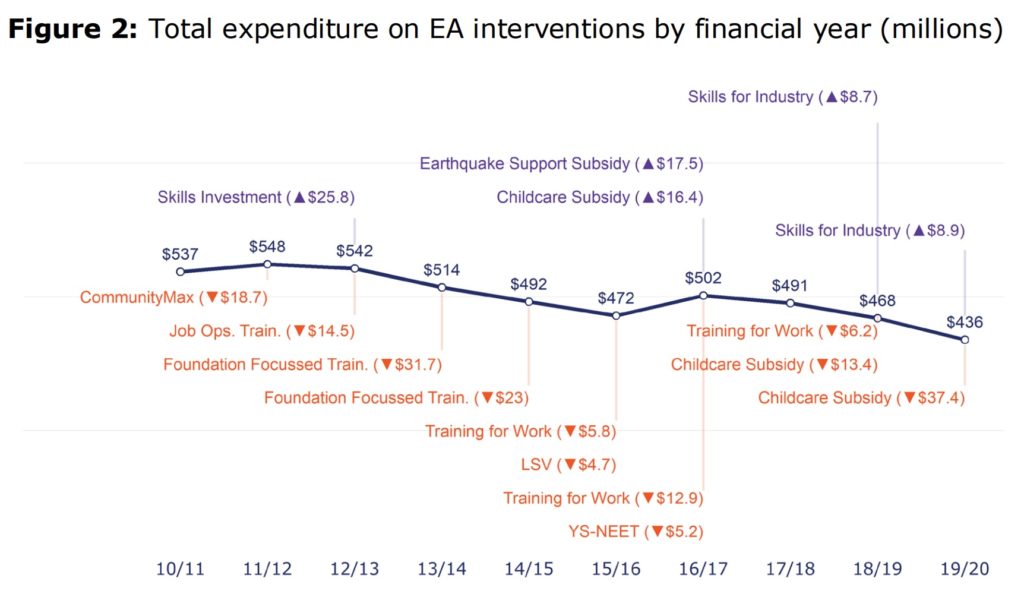

This month another MSD report which monitors the effectiveness of EA (Employment Assistance) interventions contained this graph:

The values are not CPI adjusted. If they were the declines would be steeper.

Furthermore, the commentary reads,

“…the total level of expenditure in the effective and promising categories has decreased since the high point of 2013/2014 ($192.3 million). In the last four years the fall in effective expenditure was led by the reduction in spending on Training for Work and Flexi-wage (Basic/Plus).”

So not only is less being spent on employment assistance, but what is spent is less effective.

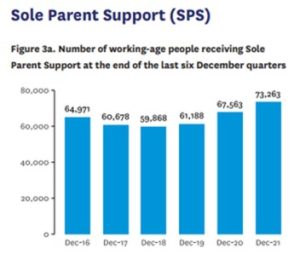

Another example of de-emphasising employment is the reversal of National’s subsequent child policy. To discourage sole parents from having more babies to avoid a job, National legislated that the parent would only get the post-birth year free from work-testing.

Labour abolished that rule. Now, as long as a sole parent continues to have children, she will not have to find work. The numbers on a sole parent support benefit are once more on the rise.

The Labour government has also discouraged full-time work.

For instance, they significantly raised the amount someone can earn without losing any of their benefit. While this superficially sounds ‘kind’ it risks an increase in people who get by on part benefit/part income from work. It doesn’t incentivise risk-taking, ambition or independence. It actually makes it harder for someone to get off a benefit.

Right now there is a desperate need for skilled and unskilled labour in this country.

Yet more people – and more children – are on welfare than when Labour became the government.

In December 2017 123,039 people were on the Jobseeker benefit and 289,788 people were on any main benefit.

By December 2021 the respective numbers had risen to 187,989 and 368,172 – increases of 53 and 27 percent.

There is one major reason for these increases.

It’s not covid.

It’s politics.

It’s political ideology and political failure.

The failure to effectively address New Zealand’s mental health crisis, despite putting almost $2 billion more into the sector, results in more people too sick to work.

Reliance on a Jobseeker benefit because of a psychological or psychiatric condition is up 48 percent in four years.

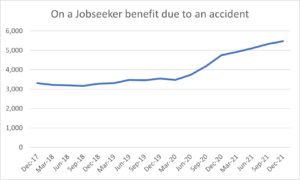

Another odd trend is becoming apparent. The rise in people reliant on Jobseeker due to an accident. This appears to be covid-related but is it also a failure of ACC?

The rise in sole parent beneficiaries noted earlier is accompanied by a 23 percent rise in associated children. Apart from easing work requirements Labour has sent a new message about paternal responsibility. The sole parent no longer needs to name the father for the purposes of collecting child support. This change was another radical departure from the Clark/Cullen government’s approach which was to increase the penalty for such a failure.

Many of these children will eventually follow in their parent’s footsteps and require intervention as young people.

But the $21.7 million going into Youth Services in 2019/20 had an effectiveness rating of ‘no difference’ or ‘negative’. Negative presumably means making problems worse. To be fair the report did assess the $9.7 million spent on Youth services for young parents as ‘promising’ but overall, the picture is of spending and effectiveness decline.

But you needn’t take my word for it.

The Ministry’s own most recent annual report stated:

“Results, in general, indicate that performance is not yet following the desired direction of travel for all indicators.”

Indeed. When Labour came to power the average ‘future years on a benefit’ was 10.6 years.

Now it is 12.4 years.

What a colossal indictment.