“On the Money” – economic, financial and political commentary by Michael Coote…

With the Jacinda Ardern-led tripartite coalition government passing its hundred day milestone in the 52nd New Zealand Parliament, Labour and National are now running neck-and-neck in public opinion polls. Either could potentially win the next general election in 2020 outright. This suggests that New Zealand’s MMP electoral system has finally produced pre-MMP first-past-the-post conditions for the first time since it was introduced in 1996. For reasons examined below, both major parties could be missing minor party coalition partners after the 2020 general election and have to go it alone in the quest to govern in the 53rd New Zealand Parliament. The era of minor parties holding the keys to power for major parties appears to be at an end or close to it. At the very least, it looks like we are headed for a two-party Parliament after the next general election.

The 2017 general election was noteworthy as a bloodbath for minor parties, defined as registered political parties apart from Labour and National. United Future and the Maori Party were exited, one by withdrawal and the other by defeat, following the example of the defeated Mana Party in 2014. Only three minor parties scraped through: Act New Zealand, Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand, and New Zealand First. The Greens were nearly tipped out over the Metiria Turei welfare scandal. A trend is observable of decline in multi- party representation in Parliament over the eight MMP general elections held to date. Table 1 summarizes Parliamentary representation statistics for the three minor parties that were returned to Parliament in 2017.

Table 1: Historical Parliamentary representation for minor parties returned at the 2017 general election

| General election year | Act MPs | Green MPs | NZ First MPs |

| 1996 | 8 | n/a | 17 |

| 1999 | 9 | 7 | 5 |

| 2002 | 9 | 9 | 13 |

| 2005 | 2 | 6 | 7 |

| 2008 | 5 | 9 | 0 |

| 2011 | 1 | 14 | 8 |

| 2014 | 1 | 14 | 11 |

| 2017 | 1 | 8 | 9 |

Centrifugal MMP between 1996 to 2014

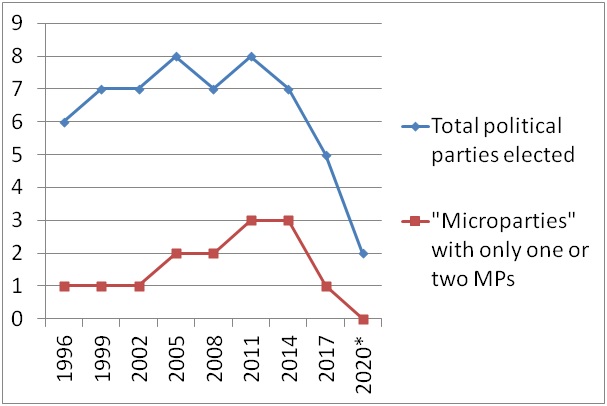

Graph 1 shows that the 2017 general election was unusual in the substantially reduced number of political parties returned to Parliament. Just five won re-election, whereas in previous MMP elections from 1996 to 2014, between six and eight parties was the norm, with seven the average. The graph has been extrapolated to show only two parties – Labour and National – in Parliament after the 2020 general election. Even if three parties were successful – including the Greens – the graph foreshadows a crash in minor party representation.

The graph also depicts the number of “microparties” with just one or two MPs. Parliamentary microparties are a dying breed, with only one, single-seat Act, still left and poised for exit. They had their heyday across the 2005 to 2014 general elections, but in many cases were symptomatic of chronic political defeat expressed in reduction to tenuous rump representation. Under MMP, single-seat party MPs function more akin to independent electorate MPs than any sort of organised political movement.

Graph 1: Numbers of parties represented in MMP Parliaments 1996 – 2020 (extrapolated)

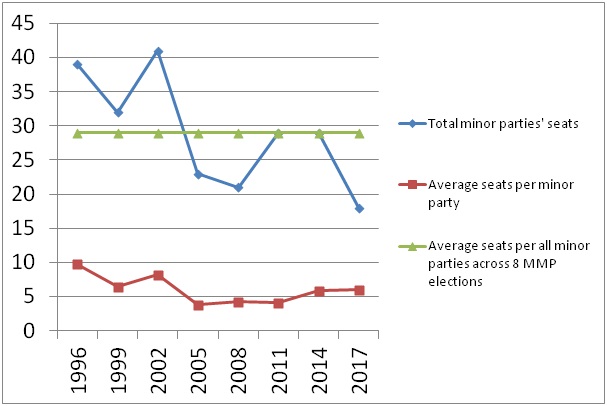

Graph 2 illustrates how the total number of seats won by minor parties has fallen overall between 1996 and 2017, despite an average total number of 29 minor party seats across eight MMP general elections, or about 25% of the 120-seat MMP Parliament. The average number of seats per individual minor party has also dwindled. Nonetheless, the period from 1996 to 2014 could be described as the politically fissiparous centrifugal era of MMP in New Zealand. The centrifugal era was typified by four to six minor parties winning Parliamentary seats – albeit with some fluctuations – giving rise of necessity to coalition governments such as MMP is intended to achieve. Minor parties enjoyed enhanced popularity as voters abandoned and splintered away from their traditional first-past-the-post options of Labour and National in search of diverse choices to the left, right, or centre of the major parties. Tactical voting played a part in casting electorate and party list ballots for minor parties with an end coalition in mind, along with willingness to conduct political experimentation.

Graph 2: Seats won by minor parties represented in MMP Parliaments 1996 – 2017

Centripetal MMP from 2017 onwards

The centripetal era of MMP was ushered in with the 2017 general election as the number of political parties returned to Parliament underwent shrinkage. Although five parties made it, only four count, with the fifth, Act, now a transient irrelevancy. Party representation in Parliament is undergoing a period of rationalisation and consolidation. New Zealanders are conservative in their support for parties regardless of personal political stripe, meaning that they vote into Parliament established political brands they know and are familiar with. Electors practice “negative selection” by voting out minor parties who have exhausted their support. By contrast they shun “positive selection” of new, untried offerings, even if well funded and widely publicised such as the Conservative Party was in 2014 or The Opportunities Party in 2017.

Minor parties voted out at New Zealand’s MMP elections historically fail to return. The sole exception has been New Zealand First, expelled from Parliament in the 2008 general election upon the campaign ultimatum of National’s then leader John Key to stay in opposition rather than serve in government with the minor party, only to return, Lazarus-like, in 2011. The 5% party vote threshold for Parliamentary representation, or one-in-twenty party votes cast, looks deceptively simple to hurdle successfully for new political parties, but in practice is difficult to breach. As the public’s understanding of MMP has improved, particularly concerning tactical voting to assist major parties to form governments, the tendency to give the benefit of the doubt to minor parties as intrinsically valuable for Parliamentary diversification has declined. Instead, minor parties have been demoted to instrumental status in determining whether Labour or National are able to govern.

Trends for the 2020 general election

The various political parties in Parliament should be pondering their tactics and strategies for a new first-past-the-post environment looming in the centripetal era of MMP. For a number of reasons, the next Parliament may well be made up of only two or just three parties.

National

Tip: Back in Parliament in 2020 and possibly forming the next government on its own.

Since the 1996 advent of MMP in New Zealand, National has been haunted by the “beached whale effect”, its own jargon for being the largest party in Parliament but without sufficient political support from minor parties to enable it to govern. National’s long-held nightmare finally came true with the 2017 election result. It is now officially the Parliamentary behemoth marooned on opposition bench shoals. The 2017 election night “winner” was actually defeated, revealing the brutal truth of MMP that victors are meant to emerge not on election night but only after subsequent coalition deals are struck. Yet the numbers game of MMP can cut both ways. Three years in opposition may simply mean National getting ready to form the next government by itself if rival political parties do not have the combined numbers they need to rule next time around.

Major risks to National under the emerging first-past-the-post scenario are smugness, arrogance, complacency, rear vision mirror fixation, and failure to refresh the line up or engage effectively with the public’s leading concerns. At present National is fronted by too many overexposed grey blurs who think they should be running the show just because they deserve to. Better they retire and glean themselves the self-congratulatory knighthoods Mr Key reinvented to that effect. With Act, the Maori Party and United Future now bust, and enmity for New Zealand First irrevocable, National has no viable coalition allies left within Parliament or elsewhere out on the political horizon, so must work out how to win by going it alone.

If it fails to devise a successful strategy to govern in its own right, National is fated to another round of debilitating internal civil wars that characteristically engulf its Parliamentary ranks after electoral defeat and faces at least six or even nine more years in opposition. Many of its newer MPs have only experienced being in government, in some cases at early ministerial rank. How they cope with being in opposition will test the resolve of many. Some pine aggrievedly for their former days of pomp. It is less than ideal for recently deposed National ministers to sound like materialistic strangers to humility singularly bent upon grasping restoration of fat salaries, cushy perks, and fawning adulation as rightful sinecures. Such an attitude could lose National party votes and marginal electorate seats in 2020, leaving it facing uncertain prospects for the 2023 general election and beyond. National’s Parliamentary opposition line up must undergo major restructuring, moral cleansing, and outright purges if it is to stand a chance of returning to power after just one term out of office.

Labour

Tip: Back in Parliament in 2020 and probably forming the next government on its own or in coalition with the Greens.

New Zealand’s most popular political asset could soon be whomever Ms Adern gives birth to in June. News media will be transfixed by Ms Adern’s triumphant ascension to rank as the country’s First Mother, simper endlessly over her adorable First Baby bundle of joy, and coo about her obliging First Husband metrosexual domestic manager manfully staying home to bring up the rugrat. Meanwhile, Jax (rhymes with tax) will courageously take up the cudgels against disempowering sexist prejudice and enervating female stereotyping. Selflessly she will sacrifice intimate household hours to a fulltime day job, all so the young family entirely dependent upon her breadwinning efforts can eke a hard-won crust from her prime ministerial salary. Somehow Ms Adern will manage to look radiantly glamorous the whole time.

Supermarket shelves will groan beneath the crushing burden of women’s magazines engorged by breathless tales of the model Kiwi family for all reproductively-inclined persons to aspire after. Ms Adern will achieve in New Zealand what Donald Trump has wrought in America by blending high public office with reality television. The nation might even be collectively invited to witness the childbirth live. There will be nigh on three years of this chaffy pabulum to endure, but Ms Adern may be onto something.

Statistics New Zealand reports that women are more inclined to vote than men and Ms Adern may have found another reason to get them to turn out for Labour by going into her own. The risks for Labour are voters getting sick of the happy families theme, with serious policy issues and major governmental achievements along the way starved for oxygen by the anointed First Family’s obtruding incessant trivia. At least Labour has struck a winsome note that National’s wizened post-menopausal male hierarchy is unable to emulate. Ms Adern also needs to rein in her tendency to sound shrill and moralizing. All up, Labour could find itself in much the same position as National in having sufficient voter popularity to aim for ruling alone, first-past-the-post, at the 2020 election, but has the additional trick of the Greens lodged up its sleeve.

Green

Tip: Marginal for being back in Parliament in 2020 because uncertain of making the 5% party vote threshold.

The Greens had a near death experience when former co-leader Metiria Turei almost destroyed their political brand with her selfish personal entitlement mentality meltdown in the lead up to the 2017 general election. The post-Turei Greens managed to claw back over the magic 5% party vote threshold, but the secret is now out that as a list-only party without an anchoring electorate MP, they are vulnerable to defeat and not an essential fixture in Parliament. Currently the Greens have no obvious chance of winning an electorate seat in 2020, so whether they remain in Parliament after then is entirely dependent on how well their closest and deadliest competitor, Labour, polls.

Electoral performance of the Greens and Labour is negatively correlated, meaning that voting trends for the Greens move in the opposite direction to those of Labour. The two parties filch support from each other, with Labour less dependent on this mutual parasitism. If the Greens cannot convert enough of Labour’s potential party vote to hit the 5% mark in 2020, they are gone for good. Labour will be out fighting with sharp elbows for every party vote it can seize under a first-past-the-post scenario, and may edge out the Greens in combat. In the interim, Green MPs have elected to co-govern as Labour’s supine rubber stamp outside of Cabinet and suffer from a particularly insipid muster personified by their currently sole co-leader, the colourless and robotic James Shaw. An internal party election is underway for a female counterpart chosen from an equally uninspiring gaggle of politically-correct Greenspeak parroters.

In the past the Greens derived a lot of their political mojo from dynamic pairings of charismatic male and female co-leaders who pitched reassuring bromides to middle-class lefty squelches, but that strategy is not likely to bear fruit this time around due to the moribund human resources available. The risk for the Greens is that they become too subservient to Labour to re-elect to Parliament as something different. For evidence of Green co-optation, look at their coalition agreement with Labour, wherein it states, “The Labour-led Government shares and will support these [Green] priorities.” By contrast, their arch-rival Labour is increasingly presenting itself as too interesting not to elect into government, as its big rebound in public opinion polls since the 2017 general election evinces.

However, Labour might see benefit in stepping aside for an electable “Labour-lite” Green candidate in the National-held marginal seat of Auckland Central, where the Greens persistently poll above their national average, in order to ensure the best chance of crushing National in the 2020 general election. That way, the Greens would have a shot at returning to Parliament as Labour’s coalition helots even if they failed to garner 5% of the party vote, all without costing Labour a seat. The Greens being pigheaded, however, they would typically respond perversely to Labour’s lifeline by insisting on putting up some nutty-as-a-fruitcake far leftist or Maorificationist zealot and go down to certain defeat in Auckland Central. Labour’s risk from the Greens is that its putative 2020 coalition partner will self-destruct as it nearly did in 2017.

New Zealand First

Tip: Gone from Parliament in 2020 because failing to make the 5% party vote threshold.

Apart from its dying breed of crabby, SuperGold Card-brandishing, one-foot-in-the-grave obdurate loyalists, New Zealand First has perennially relied upon fickle support from disaffected or tactical Labour and National voters to return to Parliament time and again. At the 2017 general election, the party lost Northland, its sole electorate seat, which means it is back to being list-only and, like the Greens, subject to the 5% party vote threshold. Unlike the Greens, who have a shadow of hope for making the 5% mark in 2020, New Zealand First looks like a party on the way out, with no realistic prospects for winning another electorate seat or at least 5% of the party vote at the next general election. New Zealand First is running on empty, losing both time and potential supporters necessary to guarantee re-entry into Parliament.

Its veteran leader, New Zealand Superannuitant Winston Peters, is the only political asset New Zealand First can rely on, and there are reasons to think he has done his dash. Without Mr Peters there is no re-electable New Zealand First, but perhaps with him the same problem has now arisen. At age 72, Mr Peters looked and sounded old, tired and crotchety both on the election campaign trail and during marathon coalition negotiations. The legitimate question arises as to whether he will still have the endurance, stamina, and enthusiasm required of a party leader to compete effectively in the 2020 general election at age 75.

Then there is the matter of trust. For voters, New Zealand First was the only political party of the 2017 general election that made a stand on rolling back the toxic tide of Maori racism that is destroying New Zealand as a functioning democracy. In this respect, the other parties in the current Parliament are kuri (ie., the dogs of Maori, with the exception of Act), insofar as they aim to promote and facilitate separate rights and privileges in law and public policy for the exclusive benefit of Maori and to the collective loss and disadvantagement of all other New Zealanders. The coalition agreement between Labour and New Zealand First achieved nothing of note in respect of Mr Peters’s oft-repeated vows to end the malign influence of Maori racism in New Zealand law. In particular, Mr Peters offered to remedy the Resource Management Act 1991 that the previous National-led government unconscionably prostituted to antidemocratic Maori racist ends under the guise of reform. The 2017 coalition agreement with Labour was surely New Zealand First’s last gasp at undoing the racialization of New Zealand society; the historic opportunity will not likely ever return and this will be the minor party’s lasting failure. Consequently, New Zealand First has ceased to be the party that voters concerned about Maori racism can vote for in confidence.

National supporters who tactically cast their 2017 general election party vote for New Zealand First had little reason to do so again once it was revealed that the minor party entered into coalition negotiations with its leader simultaneously launching unannounced legal proceedings against senior National figures. The latest conflict between the two parties is yet one more incident in a long legacy of bad blood and aggravated distrust that should ensure National never again takes New Zealand First seriously as a coalition partner. National and New Zealand First appear constitutionally unsuited to being members of the same coalition government, meaning that New Zealand First loses political credibility as a flexible go-between in general elections and becomes reduced at best to an enfeebled Labour adjunct. Messaging to National supporters in 2020 is likely to reinforce that bitter lesson in stressing that giving a party vote to New Zealand First is defeatist voting for a Labour government.

It has also emerged since the governing coalition was formed that during prior negotiations Ms Adern confided to Mr Peters that she was expectant. This intelligence may have influenced New Zealand First to entertain pregnant hopes for what might come out of a coalition with Labour, such as an extended acting prime ministership. Labour supporters who voted tactically for New Zealand First in 2017 will be much more assured in 2020 that their party votes should go exclusively to Labour to maximise its Parliamentary presence and perhaps achieve an outright first-past-the-post victory. New Zealand First seems to have entered its swansong Parliamentary term. It will need a veritable political miracle to scratch up at least 5% of the party vote at the next general election, having lost the support of Labour and National voters and opponents of Maori racism.

Act New Zealand

Tip: Gone from Parliament in 2020 because National will see no further merit in the Epsom seat accommodation.

Act only squeezed back into Parliament in 2017 with a single representative because National voluntarily declined to run an electorate candidate in the Epsom seat and advised its supporters to vote instead for the Act candidate, party leader David Seymour. Prior to the election, Act chose a high risk strategy of campaigning vociferously for five MPs (one electorate and four party list), which could only antagonise National because the party votes required for Act’s putative list MPs would have had to come from National’s share. In the event, despite heavy promotion of its five MPs objective, Act received a stinging rebuke New Zealand-wide by coming seventh in the party vote stakes with a pathetic 13,000, averaging 183 party votes across 64 general electorate seats and seven Maori electorates. Two defeated minor parties, the Maori Party and The Opportunities Party, surpassed Act by receiving over 30,000 and 63,000 party votes respectively. Even eighth-placed Aotearoa Legalize Cannabis Party scored 8,000 party votes, 61.5% of Act’s tally. If ever New Zealand voters told a returned political party in no uncertain terms to stop wasting their time and get out of Parliament, surely Act got the message in 2017.

Entailed in its doomed five MP campaign, Act undertook trenchant criticism of National, which considering the longstanding accommodation whereby National has gifted the Epsom seat to Act as political patronage, could only be construed as treacherously biting the hand that feeds. Small wonder that miffed National subsequently stated it would not be including ingrate Act in any coalition government it might form, which was clearly also pitched to appease New Zealand First. Matters were compounded by Mr Seymour’s badly written, in parts ungrammatical, election-year biography-cum-political-manifesto “Own Your Future”, a hodgepodge which was nothing short of an embarrassing read, especially for the leader of a political party that chose to campaign heavily on its education policy. Mr Seymour would be well advised to own his future by brushing up his curriculum vitae in preparation for life post-parliament.

The 2017 general election decisively proved that Act cannot rustle up enough party votes to produce even two MPs, one electorate and one party list. In case there is any doubt, this was also the result for Act in the general elections of 2011 and 2014. Act has flatlined politically and lost its one potential attraction that might have spared it rejection by National in that it plainly will never produce any more list MPs to help make up a viable coalition partner. Moreover, Mr Key, who when National’s leader was inclined to cut deals with small minor parties like Act, United Future and the Maori Party as precautionary coalition insurance policies, is out of the picture. The people running his party now are very much “National First” partisans, hostile to any competitors for the party vote. As soon as National reverses its Epsom accommodation strategy, one-man-band Act is out of Parliament. Rationally, National should cut Act loose, as it gains nothing from maintaining an estranged single-seat armchair critic sniping from the sidelines in place of a loyal sitting electorate MP who could raise huge amounts of party funds in a vastly rich electorate.

Conclusion

The centrifugal era of political party politics under MMP in New Zealand that prevailed from the general elections of 1996 through 2014 was favourable to minor parties at the expense of the two major parties, Labour and National. This period was terminated at the 2017 general election. From 2017 onwards a centripetal era is unfolding, which is ill-disposed to minor parties but revives the two major parties into contention for first-past-the-post election victories. Effects arising from the 2017 general election have reinforced the political duopoly of Labour and National as the two natural alternating parties of government, while at the same time destabilizing the remaining three minor parties – Act, Green, and New Zealand First – that made the cut to return to Parliament. At the 2020 general election, Act, the Greens, and New Zealand First will quite probably be out the door. At a higher level, the case has been demonstrated that New Zealand’s MMP system does not necessarily preserve multi-party plurality indefinitely and that ultimately voter preferences determine whether a first-past-the-post system emerges over successive party vote-dominated elections. If first-past-the-post is restored under MMP, it may be quite some time before minor parties are returned to Parliament, given the established trend for their elimination and the tough 5% party vote threshold.

Statistical source: http://www.electionresults.govt.nz/