They say a week is a long time in politics. For the Leader of United Future, MP Peter Dunne, the last few weeks in Parliament must have seemed like an eternity.

They say a week is a long time in politics. For the Leader of United Future, MP Peter Dunne, the last few weeks in Parliament must have seemed like an eternity.

His fall from great heights has been sudden and surprising. First, his party was deregistered by the Electoral Commission for failing to retain a minimum of 500 paid-up members. Then, he had to resign his Ministerial Warrants when he refused to fully cooperate with an inquiry into the unauthorised release of classified material – and more importantly continued to do so even when asked by the Prime Minister.

While he claims he didn’t leak the Kitteridge report into the Government Communication Security Bureau to the Dominion Post journalist who broke the story, he refused to supply emails between himself and her to the inquiry. As he said in his resignation speech, “some of my actions after I received an advance copy of the report were extremely unwise and lacked the judgement reasonably expected of a minister in such circumstances. I have acted extraordinarily unwisely, even stupidly, and I am now resigned to paying the price for that.”

Opposition parties have set upon Mr Dunne as a way of damaging the government. What happens next depends on whether he is able to withstand the on-going attacks from opposition parties calling for his resignation from Parliament.

There appear to be three options for Mr Dunne and National – all set within the context that National requires Mr Dunne’s support in the House to govern.

Mr Dunne could simply attempt to remain the MP for Ohariu and continue to pledge his support to National. That would of course gift the opposition with an enduring opportunity to undermine the credibility of the government. While Mr Dunne may conveniently take an extended holiday, the government cannot escape the attention so easily.

A second alternative is for Mr Dunne to resign from Parliament, resulting in a by-election in Ohariu. The seat’s pedigree is true blue and National would easily win. That means, in effect, a new National MP would replace Mr Dunne so the government’s majority would reman intact. There may be a short-time between the resignation of Mr Dunne and the by-election where National would have to rely on the Maori Party – that would require careful management of the legislative programme.

In the event that Mr Dunne did resign from Parliament, a third option open to the Prime Minister is to call a snap election.

If a snap election was held right now, the polls indicate that National would be returned to power and might even be able to govern in its own right.

In contrast, the Labour Party is said to be broke – their attempts to win support from the business sector apparently evaporated the moment they aligned with the Greens to announce their unwise plan to nationalise the electricity industry. It is reported that Labour’s internal polling shows their support falling below 30 percent. Labour leader David Shearer does not appear capable of driving the party to an election victory.

The Green Party’s popular support also appears to be waning. It could be that the wider electorate is becoming aware of their deeply socialist intentions – masked behind a friendly façade of environmentalism. More and more people are starting to recognise how radical the Greens are and how damaging they would be should they become part of a left-wing government.

If an snap election was called, the Maori Party is likely to be reduced to just one seat, the Mana Party would have one, without another cup of tea, ACT would be gone, and on current polling so too would New Zealand First – although Winston Peters could expect to increase his support substantially through the publicity he is gaining by attacking Peter Dunne.

New Zealand has only ever had three snap elections. Going to the polls early is a risk, but one politicians calculate. In 1951 National Prime Minister Sid Holland called a snap election after the waterfront strikes and National increased its majority in Parliament by 8 seats to 54 percent, compared to Labour’s 45.8 percent. But in 1984 when National Prime Minister Rob Muldoon called a snap election, National lost 10 seats and the election, dropping to 35.9 percent of the vote compared with Labour’s 43 percent.

The country’s last snap election was called by Prime Minister Helen Clark in 2002 in response to the collapse of their coalition partner, the Alliance. Opposition MPs had a field day over the break-up of the Alliance, but in the end, when the negativity started to spill over onto the Labour Party itself, Helen Clark pulled the plug and called the election three months early. The gamble paid off – Labour was returned to power with 3 extra seats and 41.3 percent of the vote, while National suffered its worst election defeat ever, falling to 20.9 percent.

Given that the economy usually features strongly in election campaigns, National is well positioned for a snap election, should it choose to call one. The response to their 2013 Budget has been positive, and the emerging economic data looks good. Our trade data is improving, we had had the best ever April visitor numbers, the largest increase in residential building activity in 10 years is now underway, and there has been a big fall in both unemployment and youth unemployment. On top of that, the tax take is ahead of forecast – with gross company tax revenue up over 40 percent – interest rates are at the lowest levels ever, and so too is consumer price inflation.

Of the options open to National, should Peter Dunne choose to vacate his seat early, the safest path is to win Ohariu and restore their numbers. Calling a snap election is a far riskier option – although National is relatively strong and a snap election would lock in a further three years to progress their busy programme of reforms, while maintaining responsible economic stewardship under Bill English. Their decision will provide an interesting insight into how risk averse National’s leaders really are.

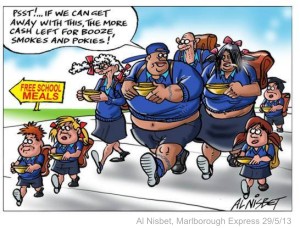

While political uncertainty is very disruptive for business and investment, it is like mana from heaven for journalists – and cartoonists. Tom Scott’s grizzly depiction of Winston Peters holding the decapitated blood-dripping head of Peter Dunne in the Weekend Herald is testimony to that. But while it seems that anything goes when politicians are the target, as Al Nisbet – the cartoonist for the Marlborough Express and Christchurch Press – recently found out, attitudes are not so liberal when it comes to social issues. Depicting people ripping off the system – especially if you show them to be Maori or Pacific Islanders – touches sensitivities.

Newspaper cartoons are meant to be provocative, and the cartoon in question showed four adults – two of them overweight and brown skinned – on their way to take advantage of the just announced free breakfast in school policy, saying, “Psst! …if we can get away with this, the more cash left over for booze, smokes, and pokies!”

This week’s NZCPR Guest Commentator Karl du Fresne, freelance journalist and former editor of the Dominion newspaper, picks up the story:

“Al Nisbet’s two newspaper cartoons on the subject of free school breakfasts brought out the enemies of free speech in droves. Remarkably, his critics included journalists, which shows how far the rot has set in. When the people who have the most to lose from the suppression of free speech are calling for someone to be silenced, we’re in deep trouble.

“The issue was whether freedom of speech includes the right to give offence, and it has long been recognised in liberal democracies that it does, and must. Even conservative judges have repeatedly upheld that principle.

“There is an insidious double standard at play here, and it was typified by the stance of the activist John Minto, who complained about the cartoon to the Human Rights Commission. Mr Minto’s own views upset and offend a lot of New Zealanders, but to my knowledge no one argues that he should be punished or silenced. Yet he seeks to deny others the right that he enjoys himself – and I suspect that he’s incapable of seeing the contradiction.”

It was John Minto, of course, who led the campaign for the sacking of TVNZ presenter Paul Henry in 2010 for implying that the former Governor-General didn’t look or sound like a New Zealander – and for emphasising the fact that the name of the Indian cabinet minister called upon to sort out the dysfunctional sewage system at the Commonwealth Games was ‘Dikshit’.

The right to offend is enshrined in our right to free speech, which is found in the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act. Clause 14 states “Everyone has the right to freedom of expression, including the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and opinions of any kind and in any form”.

However, the right to say whatever we like is tempered by the Human Rights Act, which makes it an offence to express an opinion that could be deemed to be ‘threatening, abusive, or insulting’ on the ground of the ‘colour, race, or ethnic or national origins’.

In Paul Henry’s case, the fact that he did not intend to stir up hatred, nor had any evil intent, counted for nothing. As broadcaster Lindsay Perigo said in an NZCPR article at the time, “The abiding disgrace of Paul Henry’s forced resignation is not that an unworthy standard-bearer of Political Incorrectness has lost his job; it’s that TVNZ, in shutting Henry down, has capitulated to a lynch-mob professing hurt feelings—and that hurt feelings are regarded as sufficient justification for a lynching.”1

In the breakfast cartoon case, neither newspapers nor cartoonist backed down to the “lynch mob”. They defended the cartoon and its publication. The cartoonist explained he was simply depicting how a government food-in-school programme would inevitably be abused by ‘bludgers’ – and because he saw on the news that the programme was to be run in Northland schools, “At the eleventh hour I darkened the two central characters’ skin and lips to balance the ledger. The others were white.”

His critics’ focus on the race card meant, in the words of Al Nisbet, “The whole point was overlooked… that being of a system that gave something for nothing which could be exploited by a few. How that some could plead poverty while surrounded by the unnecessary luxuries of life like booze, gambling and fags, all while comfortably ensconced within an obesity epidemic… while their children starved.”2

And that is the point. By playing the race card, John Minto – the co-vice president of the Mana Party – along with the support of his left wing allies, was able to divert attention away from the real outrage: that too many parents are failing in the most basic of their responsibilities, to properly feed their children.

Ric Stevens, the Deputy Editor of the Christchurch Press explained that newspaper editors are editors not censors, and he defended the long tradition of newspaper cartooning, stating that “They are published in the great Western tradition of free speech – to be cherished and defended”.

The Press Council has also long supported the right of cartoonists to offend in order to get their message across – a sentiment echoed by British comedian Rowan Atkinson, who was defending the ‘right to offend’ in his country a few years ago: “The freedom to criticise or ridicule ideas – even if they are sincerely held beliefs – is a fundamental freedom of society. In my view the right to offend is far more important than any right not to be offended. The right to ridicule is far more important to society than any right not to be ridiculed because one in my view represents openness – and the other represents oppression.”3

The cartoon furore has served to remind us of how fragile our right to free speech is. The media are becoming increasingly sensitive to attack, and are far more likely these days not to publish material they think might be controversial. Government officials are too ready to act – instead of brushing off the criticism of the cartoon the new Race Relations Commissioner declared it to be “offensive” – even though it did not cross the Human Rights Commission’s high threshold for racism. But with some MPs – namely the Maori Party MP Te Ururoa Flavell – now talking about the need to change the law to make the drawing and publishing of cartoons that cause offence illegal, then we know we are already on the path to the oppression described by Rowen Atkinson.

- Lindsay Perigo, The Tyranny of Umbridge ↩

- Al Nisbet, Cartoonist hits back over ‘racist’ drawings ↩

- Telegraph, Atkinson defends the right to offend ↩