State-owned energy company Meridian Energy is likely to list on the New Zealand stock exchange in October as the government takes the next step in the partial privatisation of state-owned assets. The company has now finalised a contract with the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter shareholders Rio Tinto and Sumitomo for lower priced power until January 2017 – the smelter uses 40 percent of the Meridian’s generating capacity. The deal received the green light after the government agreed to a $30 million subsidy, which has not only secured more than 800 jobs in the Southland region but has provided certainly to Meridian ahead of the government’s partial float.

State-owned energy company Meridian Energy is likely to list on the New Zealand stock exchange in October as the government takes the next step in the partial privatisation of state-owned assets. The company has now finalised a contract with the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter shareholders Rio Tinto and Sumitomo for lower priced power until January 2017 – the smelter uses 40 percent of the Meridian’s generating capacity. The deal received the green light after the government agreed to a $30 million subsidy, which has not only secured more than 800 jobs in the Southland region but has provided certainly to Meridian ahead of the government’s partial float.

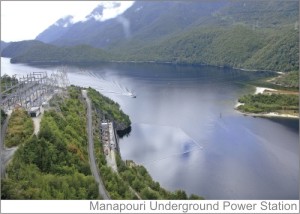

Meridian Energy is the country’s largest electricity generator, supplying over 30 percent of our total electricity needs through renewable sources. It operates seven hydro power stations and four wind farms in New Zealand, along with two wind farms in Australia, and two solar facilities – one in California and the other in Tonga. The company employs 800 staff, and in conjunction with its on-line subsidiary Powershop, retails electricity to 272,000 customers throughout the country.

Meridian is being readied for the partial sale, following the successful listing in May of 49 percent of Mighty River Power – the former state-owned power company that supplies 16 percent of the country’s electricity needs. That float netted the government $1.7 billion from 113,000 New Zealand investors. The proceeds are being used to build the Future Investment Fund, which the government expects to receive $5 billion to $7 billion in total contributions from their on-going asset sales programme. Of that, $1 billion is earmarked for heath spending and $1 billion for education.

The National Party campaigned hard on its plan to partially privatise up to four State Owned Enterprises – Mighty River Power, Meridian Energy, Genesis Energy, and Solid Energy – along with Air New Zealand, in the lead up to the 2011 election. It gained what it believes was a strong mandate from the public for the asset sales programme. The first State Owned Enterprise identified for sale was Mighty River Power, but the path to a share market listing was fraught with political hurdles.

Firstly, National’s support partner, the Maori Party, threatened to walk away from their coalition deal unless a Treaty clause was inserted into the proposed legislation. Then the Maori Council unleashed an urgent claim to the Waitangi Tribunal for the ownership of New Zealand’s freshwater. As expected, the Tribunal found in favour of the Maori Council claim, but when the government refused to give free shares to iwi and seats on the Board, the Maori Council lodged an injunction in the High Court to halt the sale. When that case went against them, they appealed to the Supreme Court. It was only when that case was rejected that the sale was finally able to go ahead.

But opponents were not yet finished.

Just days before the listing, Labour and the Greens announced their intention to regulate the wholesale pricing of the electricity industry should they become the government in 2014. This announcement created such a shockwave that the sale of Mighty River Power had to be suspended to allow investors time to back out of the deal. As a result many tens of thousands of investors who had expressed an interest in investing did not do so and many tens of millions of dollars were wiped off the value of the government’s shareholding. Within two days of the Labour-Green announcement, the share market value of Contact Energy, Trust Power and Infratil had fallen by almost $600 million.

It is fair to say that as a result of the greed of the Maori Council and the political uncertainty created by Labour and the Greens, New Zealanders lost out. The proceeds of the Mighty River sale were less than expected, so less investment money is available for spending on hospitals and schools than would have been the case if Labour, in particular, had not played politics.

The point is that people have come to expect the Greens to demonstrate their deep socialist roots and extremism when it comes to policy-making. In spite of their clever portrayal of financial credibility, even a cursory examination of their policy proposals reveal how ideologically driven and deeply flawed they actually are.

However, the markets expect Labour to produce a rational policy platform – one designed to take the country forward, not backwards into the dark ages. Yet, if their plan to re-nationalise pricing in the electricity industry ever became the law, industry experts warn that the power cuts of bygone years, would again become part of our future.

Labour says they based their centrally planned, single buyer policy on the work of Professor Frank Wolak of Stanford University, a top electricity market expert, who had examined New Zealand’s electricity market for the Commerce Commission in 2009:

“A 2009 report by international expert Frank Wolak concluded that between 2001 and 2007, the four big generators extracted super profits of 18 per cent ($4.3 billion) which came at the expense of higher prices for consumers.”1

This claim by Labour of a super profit “rip-off” was used to justify their plan to abandon present electricity market arrangements in favour of the creation of NZ Power – a Crown entity which would plan and run the electricity system, acting as a single buyer of wholesale electricity and dictating prices and profits.

However, when Professor Wolak was in New Zealand last month for a seminar organised by Victoria University, he totally rejected Labour’s claims that he had recommended a single buyer policy, calling it all a “sham”. He made it clear that the $4.3 billion estimate of ‘superprofits’ used by Labour was not his calculation, and he concluded that the electricity reforms enacted by National since 2009 were going in the right direction.2

So with the basis of Labour’s claims of super profits for electricity generators in tatters, where does that leave the debate?

Labour argues that electricity market pricing needs to be centrally controlled because household power prices are too high. However, a reality check is needed. Statistics New Zealand calculates that electricity makes up 3.9 percent of the consumers price index, but as the Herald’s Brian Fallow explains, “Only a minority of residential consumers’ power bills reflect the cost of the energy itself. Most of it is the cost of getting the energy to them, through the national grid and local lines networks, plus electricity retailers’ overheads and profit margins, plus GST – all things outside the scope of Opposition parties’ proposed reforms. So this is all an argument about whittling down what is a little more than 1 per cent of the cost of living.”3

Electricity market reforms have been underway in New Zealand for over 20 years, creating wholesale and retail markets, encouraging competition, and phasing out the cross subsidisation of household power prices by businesses. As a result of National’s major reforms in the late 1990s, real electricity prices fell year on year – until the Clark Labour Government began to re-regulate the market. Once re-elected in 2008, National re-started the reform process through asset swaps between generators, and an on-going focus on retail competition through the highly successful “What’s My Number” campaign.

Electricity is a unique commodity in that it is in constant real-time demand but cannot be stored by the generators that create it. As a result, a sophisticated electricity market has evolved that manages supply and demand at every instant in time. Electricity is traded at a wholesale level between generators and retailers in a spot market, every half-hour through 285 nodes across the national grid – 59 injection points for generators offering electricity for sale and 226 exit points for retailers bidding for electricity to buy.4

Bids and offers are signalled 36 hours before each half hour trading period, a forecast price is provided four hours before the trading period is due to start, and dispatch prices are provided half-hourly, until two hours before the start of the trading period at which point, bids and offers can no longer be altered. During each half hour trading period, Transpower publishes real time prices every 5 minutes, along with a 30-minute average price. The final price for the trade is calculated by noon the next day using the prices offered two hours before the trading period began, and the volumes established during the trading period itself.

In other words, the spot prices at each node across the country is the final price that needed to be paid to ensure that generators supplied sufficient electricity to meet the country’s demand for power during that half hour period. The final price paid is determined by the price at which the last generator met the last unit of demand during the trading period. If it were otherwise, and generators were paid at the price of their bids, then there would be an incentive for generators to bid at the highest possible price – instead of the lowest, which the present system ensures.

Max Bradford, the former Minister of Energy in the Shipley National Government and the architect of the power reforms of the late 1990s, is this week’s NZCPR Guest Commentator. I invited Max to share his view on the present state of the electricity market and to suggest what could be done to lower power prices:

“There are some things to be done to make the market work better, and put pressure on the industry to deliver the lowest possible prices to consumers. I would include the following:

- Mandating smart meters into all electricity consumers’ premises

- Consider removing metering from the generators and putting them in the hands of independent meter operators or lines companies

- Improve the ability of independent retailers of electricity to provide electricity to household consumers, by removing any barriers to their ability to buy power from generators, independent retailers or the wholesale market

- Providing a power tariff for household consumers to buy power through the wholesale market (to get the benefit of low prices when the wholesale market is over-supplied)

- Make it easier for individuals to generate their own power and supply into the grid, with a certain, if necessary mandated, tariff payable by lines or generation companies”.

In other words, his suggestions are all focused on creating more competition in the electricity market by empowering consumers. In particular, he suggests that smart meters should be owned and operated independently from generators and retailers, to give householders the ability to better manage their own power usage – including being able to buy in a competitive market from retailers, wholesalers, or generators, and to even supply power to the grid themselves, if they have their own generation capacity.

According to the Electricity Authority, by the end of 2012, 835,000 smart meters have already been installed into New Zealand homes, with 1 million expected by the end of 2013 and 1.6 million by April 2015. Through smart meter technology – along with the ripple control system which has regulated our hot water usage for over 50 years (providing consumers with a discounted ‘controlled tariff’ rate) – it is expected that home owners will be able to reduce their consumption of electricity during high cost periods to further lower their price of power.

Labour’s electricity policy has presented voters with a clear choice. Should we put our trust in bureaucrats and politicians in Wellington to run our electricity system and meet our future power needs, or should we leave it to New Zealand’s competitive electricity market, with oversight from regulators who step in when more competition is needed?

THIS WEEK’S POLL ASKS:

Do you agree with Labour that politicians should control the wholesale pricing of the electricity market?

Click HERE to see the results

- Labour Party, NZPower – energising New Zealand ↩

- Pattrick Smellie, Labour-Greens ‘nightmare’ power policy is ‘bass-ackwards’, Wolak says ↩

- Brian Fallow, Show us first that power is broken ↩

- Electricity Authority, Market ↩